Bringing Adaptation to Life: Real Stories from Africa

To many people, climate change adaptation is a complex, technical, and abstract concept. While it has risen to the top of multilateral climate negotiations in recent years, many people still struggle to understand its application in real life.

To the average African, the standard definition provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) hasn’t improved the understanding.

But away from climate negotiation jargon, what is adaptation? What does it mean to communities at the lowest level of society where the sting of climate change is most felt?

Meet Ndivile Mokoena, Sunday Geoffrey, Leonida Odongo, Patience Agyekum and Dr Michael Terungwa David. The five are members of the Pan African Coalition for Adaptation and Resilience (PACAR).

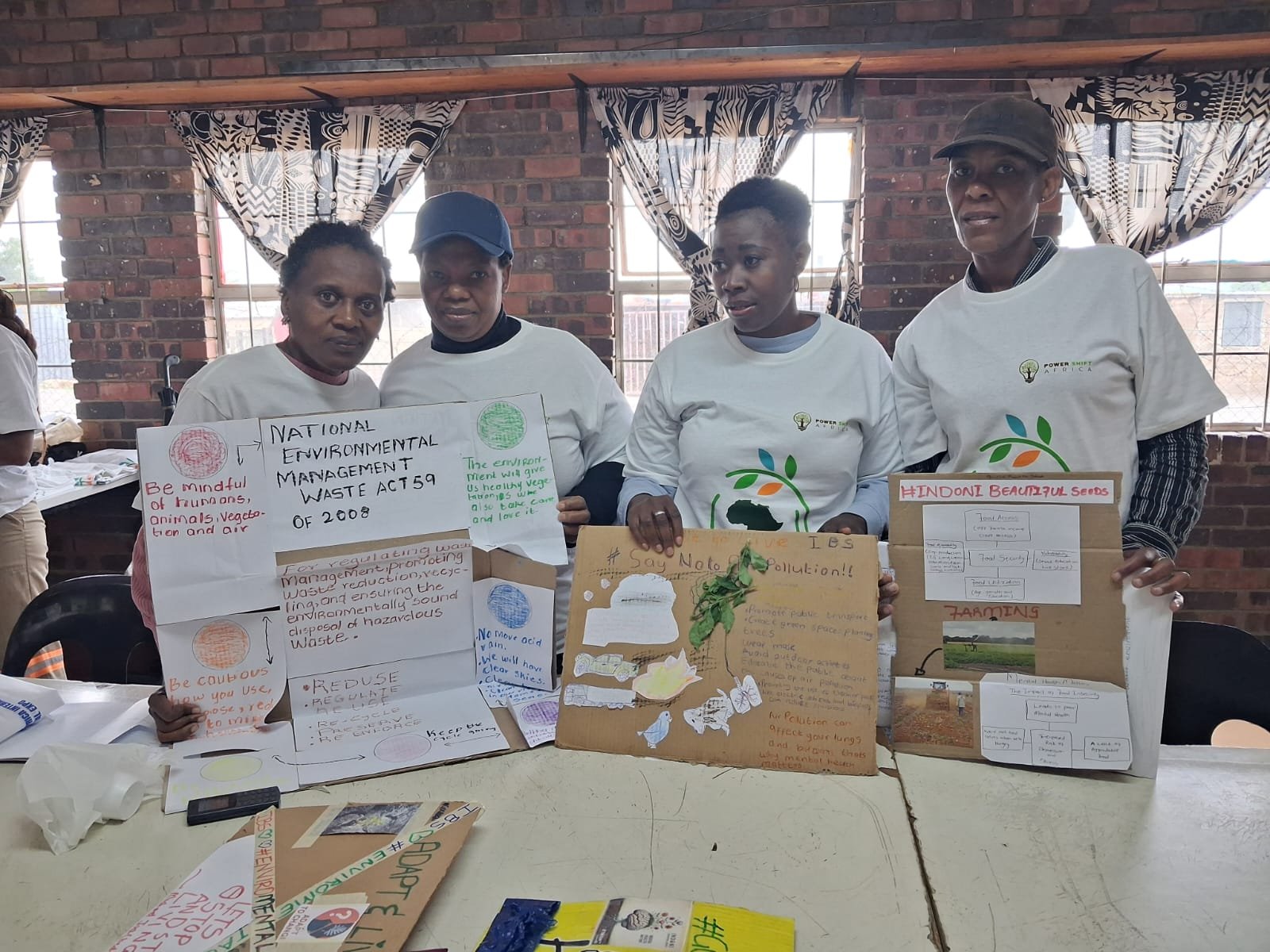

Ndivile Mokoena is the coordinator of GenderCC Southern Africa, which collaborates with communities to bring adaptation from negotiation rooms to practical application. Alexander Water Warriors in Johannesburg, South Africa, is one of the communities she has been working with in one of the most extraordinary stories of transformation in adaptation on the continent.

For decades, the community along Juskei River dumped waste into the waterway and cut down riverine vegetation. When Ndivile and the water warriors came together to sensitise the community that climate change demands a different kind of relationship between humans and nature, the state of the river changed.

By advocating stewardship and protection, the river is now cleaner, the vegetation has been restored, and water access has improved.

The serenity of the neighbourhood has returned.

‘‘Reducing effluent discharge into the river, restoring its banks, and cleaning it regularly is the only way to ensure the survival of all life forms that depend on it, including human beings. This is the basis of our message to the community around the river,’’ Ndivile says.

In northern Cameroon, Sunday Geoffrey is building the capacity of Mbororo women to practice agroecology to protect their livelihoods and food security in a warming world.

Before, the peasant women grew maize and exotic bean varieties. After multiple seasons of crop failure, owing to unpredictable rainfall patterns, the women shifted gears. To protect their livelihoods and ensure food security in a warming world, they now grow drought-tolerant crop varieties such as Irish potatoes and red beans. These are carefully selected to ensure the most suitable vines, after which mounds of soil are prepared to collect enough moisture during the wet season. They also practice mulching to protect their soil from losing moisture on hotter days.

By intercropping these with other food crops, the women have been receiving bumper harvests in recent years to meet their food and nutritional needs.

To boost their yields and income, Sunday has been advising them to consolidate their parcels to harness labour. But this faces a fundamental challenge. ‘‘Like in most African societies, men in Cameroon are the primary owners of land. Women often have limited land rights. This curtails their ability to make decisions regarding land,’’ Sunday notes.

Leonida Odongo of Haki Nawiri Afrika is a staunch believer in propagating and saving seeds of (sometimes) forgotten and neglected food crops. By working with women smallholders in rural Kenya, she helps to identify indigenous and resilient seeds at risk of disappearing. Some of the seeds they save include pumpkin, millet, and sorghum, which tend to thrive in drought-ravaged areas and are more nutritious.

Once collected, the seeds are stored in community seed banks where farmers can access them during the planting season. ‘‘Saving indigenous seeds not only preserves our cultural identity and crop genetic wealth but also gives access to farmers who cannot afford commercial seeds,’’ Leonida says.

Through her work, Patience Agyekum from Ghana has actively contributed to the formulation of her country’s National Adaptation Plans by advocating for youth representation. She and other young people recommend to the government some of the priority sectors for adaptation, including agriculture, by advancing agroecological practices, conservation of water resources, and the development of resilient settlements for communities.

This is a departure from the past, where the youth were bystanders in government decisions, often resulting in a mismatch between needs, priorities, and interventions across sectors. Patience insists that sectoral adaptation plans must reflect a development focus instead of being short-term.

‘‘Building trenches cannot be merely for draining storm water. These must be designed in a manner that addresses erratic floodwaters to protect human settlements from being swept away,’’ she says.

Meanwhile in Nigeria, Dr Michael Terungwa David of the Global Initiative for Food Security and Ecosystems Preservation (GIFSEP) is influencing policymakers to consider actions that promote adaptation for prosperity. Mike, as he’s fondly known, champions the domestication of global climate decisions in his home country by working with the government to provide climate information services to farmers.

For years, these farmers relied on the rhythm of nature to determine their farming seasons, and to predict floods and crop pests, and diseases while practicing rain-fed agriculture. Today, weather patterns are more unpredictable than ever. Pest and disease infestation have increased. In Nigeria, like the rest of Africa, farming seasons have been disrupted and yields taken a heavy hit, putting at risk the food security of not only the country’s population but also the farming communities themselves.

But there’s hope.

By providing timely weather information, farmers are now able to prepare their fields in time, know when to plant, when to apply non-polluting pest and disease control measures, and when to harvest their crops. They are also slowly embracing and adapting to these unpredictable weather patterns as the ‘new normal’.

From these diverse African experiences, adaptation to a changing climate is not different from what African communities are doing or what they have done across generations. It is the deliberateness to respond to the impacts of the changing climate system in the simplest ways at the most local level, informed by the needs of communities.

This is adaptation in practice.

Fredrick Otieno is an Adaptation and Resilience Project Officer at Power Shift Africa

About (PACAR)

The Pan African Coalition for Adaptation and Resilience (PACAR) brings together dozens of African adaptation actors working to elevate Africa’s adaptation needs and priorities. The coalition was established in 2023. Its secretariat is hosted by Power Shift Africa.