Is it time to reform the United Nations?

The old-world order has collapsed.

If it hasn’t, it’s verging on collapse.

Conflict is raging. The climate crisis is worsening. Multilateralism is limping.

Add to the toxic basket the virtually ungovernable Artificial Intelligence, widening socioeconomic inequalities, political instability, and the rising risk of pandemics and food insecurity in the world today. The list is inexhaustive.

Amid this litany of global chaos, the United Nations (UN) finds itself in a profound crisis. Many argue that the UN is ill-equipped to address the global challenges of the 21st century. This raises the question: has the world’s most powerful institution run its race? There is no consensus.

Calls to overhaul the UN to adapt it to changing geopolitical realities and address perceived inefficiencies have been floated for as long as the institution has existed. Following recent events, many believe the exercise is essential, if long overdue, for the UN’s own survival.

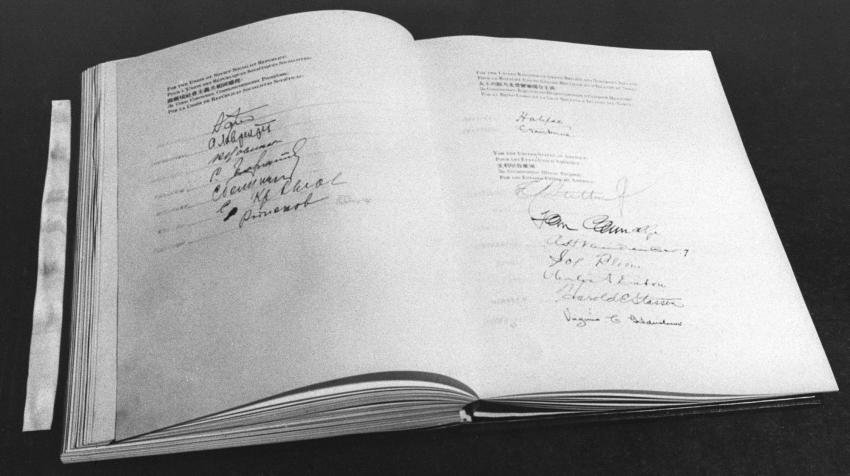

Having just been decimated and scarred by World War II in 1945, humanity needed a pact to prevent countries from sliding back into malevolence. The weight of the moment heavy on their shoulders and, perhaps, their intentions genuine, global leaders signed the Charter of the United Nations to establish the UN and, consequently, a world governed by rules and treaties, and steered forward through cooperation.

By withdrawing from multiple UN agencies last week, US President Donald Trump displayed contempt for that cooperation. Events in the Trumpian era seem to have an elastic bandwidth to daze everyone – global leaders and the ordinary person on the street alike.

For those who imagined a new, peaceful, and prosperous post-war world 80 years ago, the world would be unrecognisable in its current state. Many leaders, however, still believe in international cooperation. But they also want the UN reimagined.

To Dennis Francis, a former president of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), the expectation gap between the UN and the people it serves could be the problem.

“There needs to be a more honest conversation with the public about what the organisation can and cannot do.”

Francis says.

That conversation is already happening and will only get charged this year.

But why does the UN need reform? What would it take to overhaul the institution?

Why Actors Want the UN Reformed

Heba Aly, the director of international NGO Article 109, cites multiple factors that justify urgent UN reforms. Writing in Foreign Policy, Aly says:

‘‘A global war is a significant risk; nuclear weapons holders are openly threatening their use; climate change is making parts of our world uninhabitable; and unregulated AI risks deepening socioeconomic inequality and threatening our cognitive security.’’

These new global realities are at the heart of the push for reforms. Some feel global socioeconomic inequalities are widening, as these numbers show. Others believe the UN is opaque and exclusive, and, therefore, cannot be trusted – an unnervingly bureaucratic behemoth that isn’t fit for purpose.

War, War, War Everywhere

If the UN was established to maintain international peace and security and prevent conflict, the growing number of complex, long-lasting wars and armed conflicts around the world paints a picture of an institution struggling to fulfil its primary mandate. As of 2024, there were about 140 active conflicts globally, according to estimates by the International Committee of the Red Cross. This is twice the number of wars in 2010. From a conflict lens, the world has become worse off under the UN, argue some experts.

Number of casualties in Ukraine and Gaza

Source: Gaza Health Ministry, Other Sources

Then there’s Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the US’s January 3 invasion of Venezuela and the abduction of its leader, Nicolas Maduro, and Israel’s obliteration of Gaza. These unilateral invasions have raised serious questions about commitment to respecting the territorial integrity and sovereignty of all world nations.

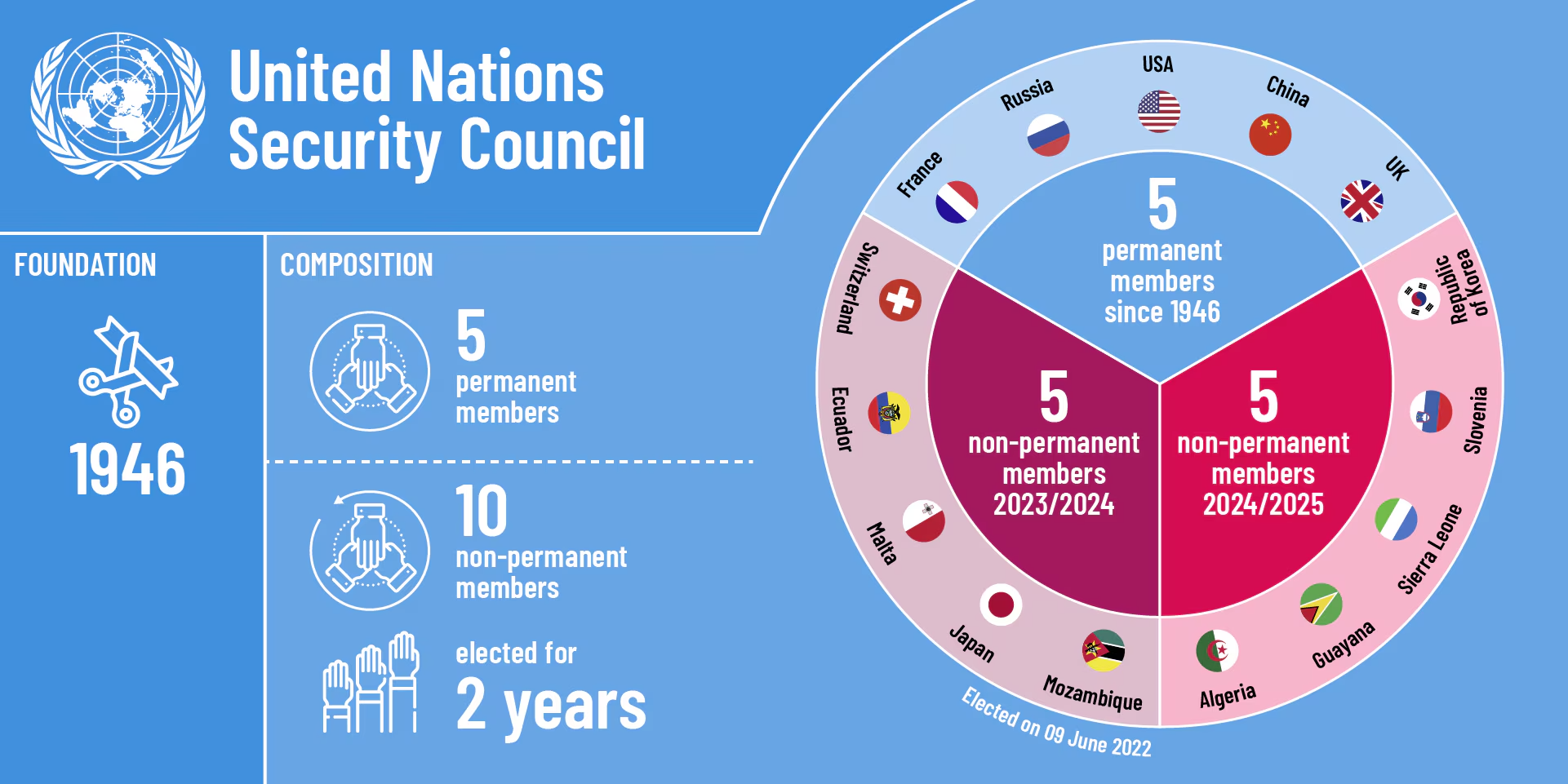

UN Security Council (UNSC)

Most of the grievances with the UN system stem from the radioactive issue of the UNSC, the arm charged with the world’s peace and security. Many opine that the UNSC structure doesn’t reflect today’s global power dynamics. The five permanent members, or the P5 (US, China, UK, Russia, and France), along with their veto power, are too ‘‘strong to manage’’. One permanent member of the UNSC is more powerful than all the 10 non-permanent members combined. Accusations of abuse of power are rife.

In the high-stakes geopolitical game of power, veto influence has traditionally been exercised along a specific plane: The United States has often vetoed resolutions regarding Israel and Palestine; Russia does so to protect its interests in Syria and Ukraine; China vetoes decisions to align with Russia. Only France and the United Kingdom have not vetoed a UNSC resolution in 36 years.

Bypassing resolutions of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) is another of the council’s faults. While the UNGA has passed two resolutions on Gaza and six on the war in Ukraine, for instance, the UNSC has passed none.

‘‘The security council has not lived up to its expectations in delivering its mandate,’’

says Dennis Francis, a Trinidadian diplomat and former president of UNGA.

Calls to create a permanent seat for Africa at the UNSC have gone unheeded, leaving the continent with more than 54 countries to settle for the less lucrative, rotational non-permanent seat in the council.

Attempts to expand the council have been largely moot. Italian economic and political theorist Daniele Archibugi argues that merely increasing the number of UNSC members doesn’t make the council more ‘‘functional’’.

‘‘Enlargement might make the Council more representative, but there is little indication that those who hold seats act on behalf of their regions,’’ Archibugi says.

Who Wants the UN Reformed?

It’s a mixture of actors. National governments (Member States), Regional bodies like the African Union (AU), civil society groups, NGOs, and reform coalitions all want the UN to be reformed to meet and effectively respond to the current geopolitical realities.

To Kenya’s President Ruto, reforming the Security Council ‘‘is not a favour to Africa or to anybody’’ but a necessity for the UN’s own survival.

“If the United Nations is to remain relevant in this century, it must reflect today’s realities, not the postwar power arrangements of 1945,” President Ruto told the UNGA last year.

President William Ruto addressing the UN General Assembly in New York. PHOTO/PCS.

Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley likens the UN’s operational manual to ‘‘the law of the jungle’’, noting that it ‘‘does not guarantee any of us a future or a liveable planet’’ and calls for a set of rules to govern the world.

Says Mottley: ‘‘Countries of different sizes, capacities and cultures can only survive in the world in which we live if we maintain a rules-based system.’’

Reform calls have also come from within the UN itself, underscoring the urgency of the task.

Leading this push has been UN Secretary-General António Guterres. ‘‘We cannot effectively address problems as they are if institutions don’t reflect the world as it is. The UN must be ready to change,’’ Guterres told the UN General Assembly in 2023, a position he restated in 2024. “It is time to consider revising the UN Charter comprehensively.’’

Guterres: ‘‘It’s reform or rupture.’’

Does the UN promote Representation or Mere Observation?

The question of the underrepresentation of Third World African, Asian, and Latin American countries in the Security Council is the shadow that follows the UN everywhere, including at its meetings.

‘‘You cannot claim to be the United Nations while disregarding the voice of 54 nations. It is not possible,” President Ruto reminded the UN in 2025.

When the UN came into existence nearly a century ago, many countries in these regions were still under colonial rule, a fact that long changed.

‘‘Africa cannot continue to be the subject of Security Council decisions without a voice at the table. We demand representation, not observation,’’ said former AU Chairperson Macky Sall of Senegal.

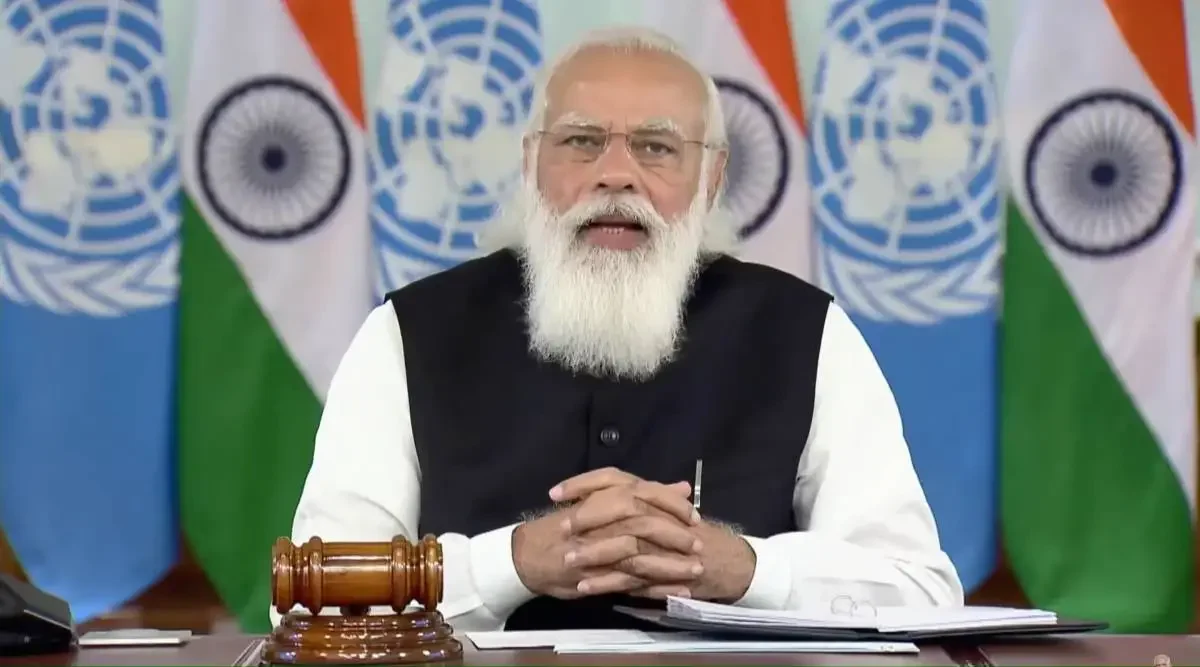

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi puts it more bluntly:

‘‘The UNSC reflects the mindset of the century we left behind.’’

PM Narendra Modi at a UNSC High-Level Open Debate. (Photo: Screengrab/Youtube@Narendra Modi)

Collectively, these issues make the UN ripe for ‘‘more than a reset’’, she says, proposing a radical surgery of the institution.

‘‘UN reform processes underway today focus on agency mergers, processes, and cost-cutting – very few address the fundamental dysfunction at the UN,’’ Aly adds.

Can the UN navigate its Constant Cash Crunch?

The United Nations faces constant cash flow crises owing to delays and underpayments from some member states. Major contributors such as the U.S. and China are notorious for delaying payments to the body, which undermines its operations, including humanitarian work and peacekeeping missions.

As of 2025, the US owed the UN $3.5 for both its regular and peacekeeping budget. Major global powers have often exploited the UN’s liquidity crisis for leverage and to exert their influence.

Ironically, the US will be spending nearly $1 trillion on defence and war this year.

Slashing the UN’s operational budget has featured in the ongoing reform debate, notably the ‘‘UN80’’ reform initiative proposed by Secretary-General António Guterres. Countries want the institution to be more efficient and to spend less, although it says steep budget cuts will have serious implications, including job losses and delayed humanitarian interventions.

‘‘The impact of aid cuts is that millions die,’’

says Tom Fletcher, the UN’s head of humanitarian affairs.

UN observers, however, argue that merely slashing budgets is insufficient to address serious structural inefficiencies within the institution. To experts, while the current UN financial approach is unsustainable, its bureaucracy only worsens the situation.

The late UNSG Kofi Annan shared this sentiment, calling for a nimble, efficient, and effective institution. ‘‘[The UN] must focus more on delivery and less on process; more on people and less on bureaucracy,’’ said Annan, a position shared by Guterres.

Still, Fletcher thinks there’s a way out. ‘‘All we ask is 1 percent of what you [spent] last year on war.’’

What Stands in the Way of UN Reforms?

Quite frankly, a lot.

From divergent national interests to lack of political will, bureaucratic inertia, funding challenges, and regional rivalries, there process of reforming an institution like the UN is beset with multiple complexities.

Foremost, amending the UN Charter requires support from at least two-thirds of the General Assembly. The resolution must also be ratified by all the permanent members of the Security Council.

Therein lies the biggest hurdle of them all.

As the global centre of power, the P5 would veto any decision seeking to diminish their control. Says Guterres: “Those with political and economic power are always reluctant to change.’’

In today’s fast-changing world, politicians in global powers are shifting to national priorities to appease their electorate, making engagements within the UN multilateralism a matter of choice. The US’s Make America Great Again (MAGA) is a case in point. When countries look inward rather than outward, the UN’s role in global collaboration on issues such as climate change is put on the balance. Even its indispensability is questioned, as the popularity of other multilateral forums such as BRICS and the G20 grows.

Eighty years later, many around the world agree that the UN is ripe for reform. To diplomats, this exercise is a hairy ambition, even unthinkable to others. But one fact is undisputed. The institution that billions across generations have come to associate with global order is crumbling under the weight of internal and external pressures.

Its outgoing Secretary General understands the importance and urgency of reimagining it.

‘‘Without reform, fragmentation is inevitable.”

Could 2026 be the year when the long road to these reforms finally begins?